Recognizing Sun Worship

Contextualizing an image of Native American sun-worship from a French Calvinist Commander and would be colonist of Florida.

First, when I speak about recognition, I am talking about representation. I am thinking about sixteenth and seventeenth century people projecting what is familiar to them onto the cultures they encounter in other parts of the Atlantic world.

For today’s reading assignment, I have given you three things:

First, some historical context to ground you in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The introduction to Bodin’s Demon-Mania, outlines key events of the time period that will explain the logics of his strange, yet also very popular and widely read book.

Noting important date ranges, what social, political, and cultural events does the author, Jonathon L. Pearl think are important?

Second, read the Jean Bodin chapter provided, noting where the information Pearl provided helps ground you in the work. Also, pay attention and Google the cultural references he makes around sun worship. I am hoping you will be able to discuss what you research in class.

Notice ancient examples. Notice the American examples.

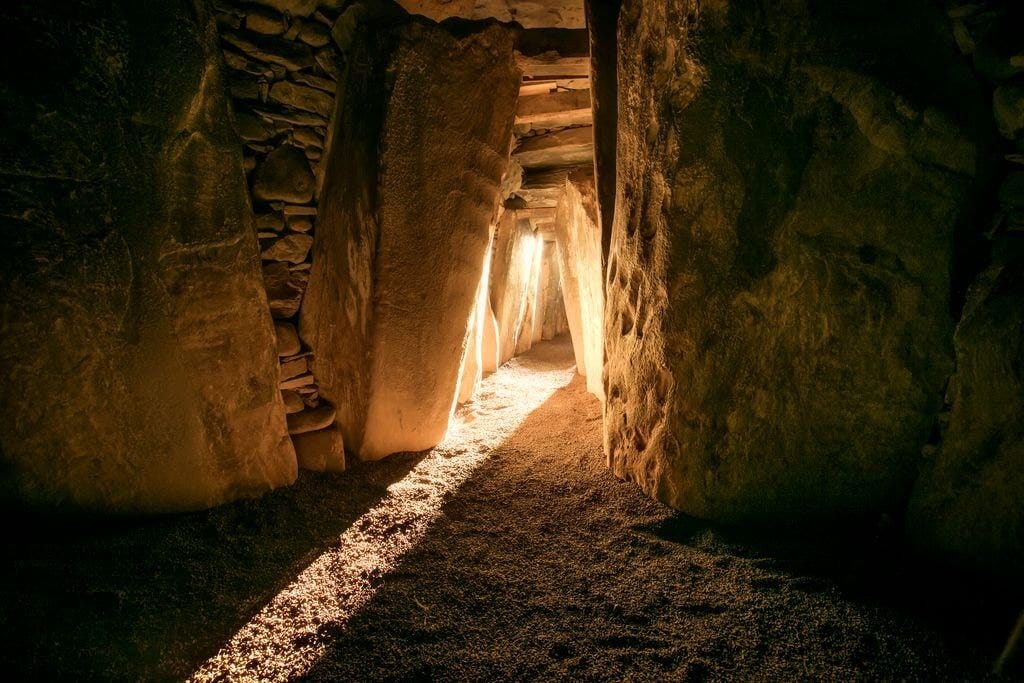

Third, I have provided images of Newgrange, below, as well as Miranda Green’s brief discussion of how this Neolithic structure and others, such as Stonehenge, indicate that “early man may have regarded and venerated the sun.” As we talked a little about in class, how would living near British and European sites such as these have caused early modern people to think about those who came before them?

As I mentioned in class, the going argument, championed by Tudor scholar Ronald Hutton, is that Christianization wiped out ancient land-based spiritualities in Europe and that there were no “pagan survivals” in early modern Europe.

Hutton and other scholars of early modern Europe note that as part of the “Renaissance” of the 16th and 17th centuries, ancient sources on Celts, Gauls, and Druids were being discovered and mass produced through new printing technologies. As early modern European nations began to define national character, they drew on these sources to understand their histories, identities, and relations with land, as Indigenous peoples of France, Germany, Britain, etc.

Although many academics and pagans cite only Hutton on the question, there are many other experts in Celtic Studies who disagree and show evidence that ancient Celtic and Gaulish beliefs were maintained in various locales throughout Europe.

For those living near huge mound structures like, Newgrange, they thought a lot about the history of ancient peoples of their region. One example, is the people remembered as the Tuatha de Danaan (children of Danu), sometimes known as the Sidhe (Aos Sí = people of the mounds) and as fairies. According to Celtic lore, these ancient people occupied Ireland before humans, called Milesians, who invaded later. They are associated in the lore with Druidry, with natural magic, and with great earthly abundance (kind of like the Fisher King in the well maiden’s story I read to you in class), who left the earthly realm to live in the Underworld. Can you imagine how Newgrange invites the idea of a powerful people leaving the surface of the earth to live underground, as would other natural formed places, like caves, and human made structures?

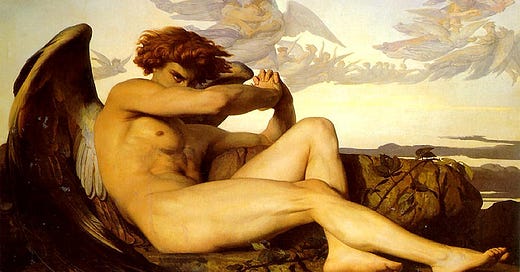

Christians would associate these Sidhe and the Tuatha de Danaan (sometimes seen as gods, fairies, and spirits of the land in a land based pre-Christian cosmology) with demons and the Devil. Christians associated the Devil with Lucifer and demons with fallen angels who kept occult or secret knowledge of nature and could manipulate it to predict the future, create illusions, and to create change, in the weather for example, such as a tempest. These demons seduced weak people who wanted that knowledge to carry out vengeance, out of greed, and, out of dangerous curiousity.

How is Bodin referring to his belief in angels, demons, and the Devil in the chapter you read? What is his motivation in discussing them? How does he think of Native American spiritualities in this context?

How do you imagine early modern Europeans would have felt about land relations and relations with the sun given the presence of Newgrange, Stonehenge, cave art, and other monuments created by ancient peoples indigenous to that land?

Finally, here is an image of sun-worship from a French Calvinist Commander and would be colonist of Florida I have studied and written about in my book, Deadly Virtue: Fort Caroline and the Early Protestant Roots of American Whiteness (2019). The engraver of the image and the French Commander are recognizing sun worship. Note the relations of power and positions of body. Not only are the Indigenous people represented as vulnerable to beliefs Bodin associated with Devil worship, aren’t the French also? Why is this slightly romantic and homoerotic? For example, why are we seeing the French commander from behind, in such revealing pants? We will discuss this further in class after considering what you learned and researched in the assigned readings.

To see discussion of this post, please follow this link to an earlier version of Atlantic Entanglements.

Readings for Week 1

Jonathon L. Pearl, “Introduction” to Jean Bodin, On the Demon-Mania of Witches (1580). Provides introductory information to contextualize Jean Bodin's On the Demon-Mania of Witches (1580).

Jean Bodin, “The Difference Between Good and Evil Spirits” 1:3 in On the Demon-Mania of Witches (1580). A chapter in which Bodin makes connections between sun worship in preChristian Europe and Indigenous spiritualities in America.

Miranda Green Light, Sun, Tombs In The Sun Gods Of Ancient Europe. Discussion of archaeological interpretations of Newgrange and other such Neolithic sites.

RECOMMENDED READING

Course Syllabus. This Substack provides a place for University students to discuss readings on sixteenth and seventeenth century cultural history. Here is the course syllabus.

I can understand why the sun worship seemed frightening or "unholy". It was easier for the colonists to think that Native peoples were dumb. Why are they worshipping the sun? What does the sun do for them? The colonists had their God and they believed that was the only god.

Bodin seemed to have a very extreme take on the sun worship. He claimed it to be demonic and evil. In the chapter about sun worship, he often talks about how people are tricked by the devil. I thought it was interesting that Bodin seemed so deranged, but he was a well respected person in that time. The Demon Mania book is ignored in his work.

When it comes to places like Newgrange, it easy to think people in this age were not smart. If you look at how these structures were built, there was A LOT of thought put into them. The sun comes perfectly through the window and into the back of the chamber on the solstice. It's obvious that the sun was important. Sun worship still happens today. I think it's cool. The sun is very important to daily life. Even if I don't worship the sun, it is one of the reasons we are alive.

This article explores how early modern Europeans viewed their ancient past through structures like Newgrange and Stonehenge and how these influenced their spiritual and cultural ideas. Living near such monumental sites likely inspired a mix of reverence and curiosity about those who came before them. This curiosity intersected with Christian beliefs, which often framed non-Christian spiritualities as dangerous or demonic. Bodin’s *Demon-Mania* reflects this, portraying practices like sun worship or Native American spiritualities as connected to the Devil and dangerous knowledge.

The reading emphasizes how Christianization reframed older land-based beliefs, like those associated with the Tuatha de Danaan or Sidhe, as pagan remnants or outright heresy. These ancient beliefs often revolved around the sun and land, elements seen as powerful and sacred by ancient peoples but later linked to occultism or demonic influence by Christians. The images and historical context also highlight how European explorers, such as the French colonists, romanticized Indigenous practices while simultaneously fearing their spiritual power. This mix of admiration and othering reveals how power, culture, and spirituality intersected in shaping early modern European identity.